Tell us about the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW): what led to their formation, what were their perspectives, and what set them apart from other revolutionary groups of the time?

The League of Revolutionary Black Workers came into being in the Detroit of the late 1960s as a consequence of the general unrest in black America that generated the most dynamic period in the black liberation movement. The League’s particular history was shaped by the Great Rebellion of 1967 (the most costly to that date in American history), the radical traditions of the city, changes in the auto industry, and the intense racism that had characterized Detroit since the early 1900s.

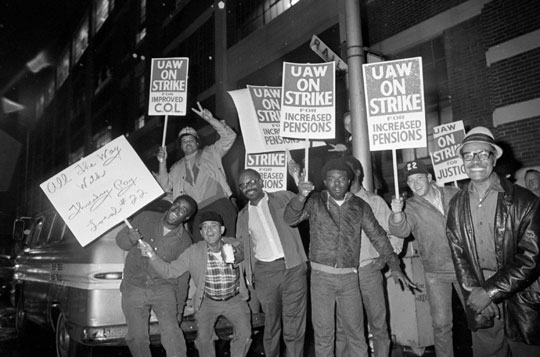

The League’s focus on organizing industrial workers and its non-hierarchical organizational structure differentiated it from other major activist groups. Young black radicals had been agitating for radical reforms in the United Auto Workers (UAW) and Detroit for years. The Great Rebellion left the black community seeking a permanent end to its second-class status. Beginning with a newspaper titled The Inner-City Voice and on site organizers, the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement was formed at Dodge’s main assembly plant. In May 1968, DRUM led a wildcat strike of more than four thousand workers. It raised socialist and Black Power demands. Numerous RUMS soon formed at Cadillac, UPS, Ford, and elsewhere. Some student and community groups also affiliated. The organization then coalesced as the League of Revolutionary Black Workers.

Economic crisis has produced increased forms of left and right populism, as well as economic nationalism that could point to a movement for re-industrialization. However, we are in a different context from the Detroit of the late ‘60s, where industrial workers were 35 percent of the working-class. Yet, even back then it was difficult to win workers over to the perspective of the LRBW: fighting for control at the point of production as a step to control the economy. Does this perspective still have a place in an economy where the service sector has grown in importance for economic activity and unionization?

The mass manufacturing base in Detroit, like many in America, no longer exists, but many of the perspectives of the League remain relevant, not as a model to copy but as an orientation to consider and refine. Primary to the League’s concentration on the working class was that organized radical workers could change society far more rapidly and effectively than the street people the Black Panthers focused on or various student movements. Such a mass industrial base does not exist in 2016 but if we use an expanded definition of workers that takes in all salaried Americans, a vast majority of the population are workers. Many of these present workers are “white collar,” considered themselves professionals, and have no union history. Radicals have made few efforts to organize these groups and usually focus on fast food workers rather than high tech workers.

John Watson, one of the League’s leaders, frequently noted that if only the black workers went on a general strike, society would be immediately paralyzed. The relevance for today is that focusing on workers at every level (not just manufacturing or even agribusiness) could have the same effect. For example, if all adjunct faculty in America went on general strike, most universities would be closed as adjuncts teach 80 percent of the classes. Longshore union strikes can and still stop shipping. Radicals need to have the imagination to understand that control of mass production is still possible even if the actual means of production differ greatly from the past. The whole realm of workers in electronic communications has not been addressed. Workers have a power they are not using.

Another vulnerable area in modern production not fully explored is the on-time production process. Stopping any one segment of that process or throwing off the timing would be highly effective. We need to think about what tactics would be effective.

The critique DRUM had of the labor peace arrangements of the UAW in the 1960s and 1970s was echoed elsewhere in wildcat struggles and an increase in public sector unionism, but unionization rates and strike activity have been down since. Do you see any openings today to the DRUM approach, taking community struggles against racism into the workplace, directly confronting management and challenging corporate power?

Too often, when one reads of organizing workers, the focus is only on the workplace. The League was very conscious of seeing workers in a broad context. Workers were immediately connected to housing issues, public education, medical services, and the entire agenda of personal/family advancement. Ultimately those problems can only be resolved with a general restructuring of society. That perspective needs to be part of any movement that would turn a significant number of the nearly 10 million Bernie Sanders voters into a dynamic, socialist movement.

Another way in which the League differed from organizations such as the Black Panthers is that the League did not to set up chapters in a traditional hierarchical structure with the League leaders as the national leaders. To the scores of local organizations that sought affiliation, the League responded that each city or region had to organize according to its own sense of local conditions as determined by local leaders and activists. When there were enough of these organizations with significant supporters, a national Black Workers Congress could be formed as a federation rather than a vanguard party.

The League chose this course because it did not want to be in the situation where a local over which it might have only minimal and distant contact could take an action that hurt the organization in Detroit. The League also reasoned it did not know the local conditions any group had to deal with and had no formula they wanted everyone to follow. Security was another major concern. The League leadership was never penetrated by the police or federal agents due to careful scrutiny of members close to the leadership. That would not be possible with a national organization, especially given the limited numbers of top organizers. Today’s movement builders would do well to bear these concerns in mind when expanding and recruiting.

Worthy of note as well is that the League deliberately had a six-person leadership. This made it difficult for the authorities to thwart the League by targeting one person. Illnesses or other personal matters that affected leading individuals would not cripple the organization. The multi-leadership ideas also served to curb the emergence of any one person in a de facto cult of personality. On a practical level, the equally powerful leaders had areas they specialized in but with accountability and discussion with the others. This placed more power and responsibility on local units.

In addition to organizing factories, the other fundamental activity of the LRBW described extensively was the publishing of their newspapers, Inner City Voice and South, as tools of spreading their struggle. Given the importance of new media today, do you think there is still a role for using a paper to organize in the manner used by RUM organizations, or has new media replaced them? What aspects of their use of a paper for organizing be taken into new media?

Like most civil rights group, the League understood the importance of media and that mass media was a creature of the capitalist class. The only long-term option was to own or control media that could reach a mass audience. In that era, this took the form of mass circulation newspapers, book clubs, book stores, making independent films, and related activities. Today, there obviously would be more emphasis on social media. The constant is that League media was less concerned about speaking to truth to power than reminding people they had real power when they knew the truth. In that sense, they continued the old IWW dictum “to fan the flames of discontent.” Among the means the League used to deal with distortion of its message was to gain control of the Wayne State University campus newspaper and turn it into the city’s third daily with thousands of copies with radical content going out daily to factory gates, laundromats, hospital waiting rooms, PTA meetings, and the like. The League spoke of having socialized a capitalist organ with the added bonus of being paid by the state to agitate against the capitalist order.

Dan Georgakas at Left Voice’s panel at the Left Forum “Shut it Down: Black Struggle, Class Struggle.”

Much has changed in terms of organizing on the ground since you and Marvin Surkin wrote the “Thirty Years Later” chapter of the updated edition. We are going through a period where Black Lives Matter has the potential to increasingly radicalize youth, and Detroit was frequently in the news for its bankruptcy in the last few years. What are some of the lessons that a new generation of activists might take from the LRBW?

Mike Hamlin, a member of League leadership, always stresses that the League’s socialist perspectives were not necessarily shared by all of its members. The League leaders had met with Che Guevara in Havana and New York. Some had been prosecuted for rioting charges. Some had supported Robert Williams’s RAM movement. These factors were known to black workers who led far more ordinary lives. They supported the League due to the bravery, integrity, and competence of its leadership in demanding and achieving changes in the workplace. In due course, the leadership believed the members would become more ideologically oriented. This would result primarily from direct action rather than talk and radical images. Small victories workers could see were far more powerful than defeats following some heroic action.

One League slogan was “U A W means You Ain’t White.” Most workers understood that was not literally true but it was true that the UAW leadership had not fought to get black workers in the highly paid skilled trades and had not promoted many blacks to high posts in the union. So the slogan rang a bell. Another effect slogan arose when a black worker killed three other workers on the factory floor. The slogan raised was “Chrysler Pulled the Trigger,” meaning conditions in the plant had caused the shootout. The case was won. The League, in short, set the agenda rather than just responding to agendas set by the system.

Radical theorists wanted to know if the League was a caucus within the UAW or the seeds of a parallel union or some other theoretical construct. The League leaders, however, were not greatly concerned with such theory. They would fight within the UAW to get full black participation and if possible gain leadership of the union. If they did not succeed, they would stay in the UAW but oppose its policies, including activism well beyond the factory gates in various venues of the black liberation struggle. They were pragmatic. They wanted revolutionary change and were not concerned if it fit into some predetermined theoretical model.

Detroit, I do mind dying, almost 40 years after its original publication, was recently released in its French edition recently. What are the circumstances that led to this development or other international interest?

I think one example of the League legacy is that the views of the League presented in Detroit: I Do Mind Dying now in its third edition (Haymarket Books) has remained in print for decades. The book also was published in France this past year. I think the book has had legs because it provides details about many topics I’ve touched on briefly. Americans are infamous for their political and cultural amnesia. Detroit is routinely cited as an example of post-industrial society, but as Detroit: I Do Mind Dying shows, the underlying cause was capitalist abandonment which is part of the new economic world order in which local sovereignty is irrelevant. In the case of Detroit, the richest urban center in America that boasted a fine school system and two million residents was transformed into the poorest urban center in America with a school system that is nationally ranked as the worst. The population has plummeted to 700,000. At the same time car production is at a historic high of 16 million as are corporate salaries and the gap between executive pay and worker pay. There is no post-industrial society in general but a shift in where and by whom products such as automobiles are made. Executives are still financially awarded for lowering wages and safety concerns. New generations of Americans and activists in other nations would benefit by learning what really happened to Detroit and the available alternative paths that were not taken.

You might be interested in VIDEO: Panel, “Shut It Down: Black Struggle, Class Struggle”

Interviewed by Michael Lynch