Author of dozens of books, and tons of articles, Stanley Aronowitz has been able to combine academic work with political activism. His book The Death and Life of American Labor touches on issues that warrant serious debate among the Left in the U.S.

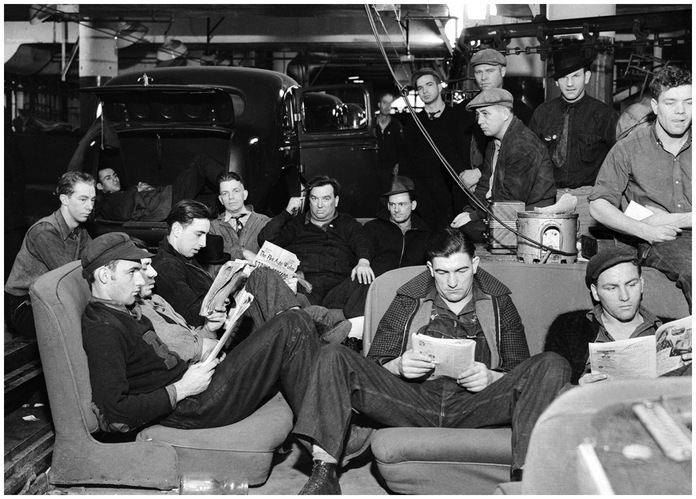

In this engaging and provocative book, Aronowitz places labor unions firmly at the center of discussion, presenting an uncompromising critique of union bureaucracies that now serve as “supplicants of the Democratic Party and depend on the electoral system to resolve workers’ problems.”

According to Aronowitz, union bureaucracies have caved time and again, particularly through collective bargaining agreements to employers’ attacks on labor over the past four decades; long-duration contracts, no-strike clauses, two-tier wage systems and increasing monetary contributions by workers into healthcare and pension plans.

The main reasons behind these concessions are unions’ fears of relocation and their “sacred respect for the law.” Instead of focusing on building workers’ power and contesting the bosses and the state through direct action, their efforts have been aimed at convincing Democrats in office to pass protective laws or soften the blow of attacks on labor.

In the author’s view, unions have dug their own graves, no longer able to “convert from a service organization to a fighting force.” Aronowitz also asserts that, although once beneficial to workers, collective bargaining agreements today only benefit the bosses.

However, taking this position, the author is in a sense tossing the baby with the bathwater. It is true that most collective agreements today include a no-strike clause and are ridiculously long (3, 4, 5 years!), undercutting workers’ ability to wage war against the boss. But this is not a necessary component of the agreements.

There is a conflation of the tool of collective bargaining and the varying negotiation outcomes themselves. I would argue against painting all contracts as homogeneous conquests for bosses. I wouldn’t assert either, as others have posited , that a contract automatically signals a defeat for the bosses.

Although laws and regulations are bourgeois and therefore play the game of capital owners, the total absence of legal rights is even worse for workers. Binding the employer to a written contract to respect workers’ conditions and payout of benefits is better than naught.

The problem, of course, is when the right to strike is given up, or when other concessions, such as two-tier wage systems or benefit cuts, are slipped into the agreement. I would argue instead that this is better understood as a product of the relation of forces between labor and capital, and of decades of business unionism, rather than the inherent pitfalls of collective agreements.

Technology and Labor, a Barren Marriage

When discussing technology and the automation of industrial production, Aronowitz disputes the liberal and right-wing doctrine that hails technological development as intrinsically beneficial. He further explains how these developments have, in fact, proven to be harmful for the working class, causing the loss of jobs, worsening of working conditions and the weakening of workers’ workplace bargaining power, to use Erik O. Wright’s term.

In addition, the restructuring of work brought about by technological innovation has deepened the divisions between low-wage, “unskilled” workers, and the professional stratum. Aronowitz points out new opportunities for the labor movement that came out of increasing proletarianization and the strategic positioning of engineers and computer scientists who, by the 1970s, “were no longer independent entrepreneurs, but had become employees.”

He argues that the professionals who make the machines work are now in the position to disrupt production: “[T]he need for effective action and organized support from and among the professional working class will soon be urgent, for we can expect further spread of almost completely automated production processes in the near future.” He envisions a world of production that is massively automated and proposes a focus on professionals and even managerial workers (!) as a key sector to unionize and win over to revolutionary politics.

Consequently, he pays little attention to the organization of low-wage workers, such as retail workers who make up about 10% of the U.S. labor force. One may wonder if this omission is warranted; recently, we’ve seen examples of actions led by the most oppressed and exploited sectors of the working class. The anti-police brutality movement propelled by black youth and the fight for wage increases by retail and fast food workers demonstrate the potential of “unskilled” workers. In an interview with Left Voice, Charlie Post makes the case for organizing low-wage warehouse and distribution workers at supply-chains for big box and fast food companies.

Union Reform versus Radical Unionism

The author makes an excellent point that union reform alone is not enough to reverse the fall in power of the labor movement. It’s not just about democratizing the unions (although in itself an enormous task): it’s about building a radical “militant minority” of workers, who will form an organization that goes beyond trade-unionism and criticizes the whole capitalist system. Hence, the author continues, the need for a political organization capable of “educating, agitating and organizing resistance to labor decline”.

Recovering the example of the 1920s Communist Party-backed Trade Union Education League (TUEL), he calls for the formation of a circle of intellectuals whose main task would be to educate labor activism. He proposes a political-educational space shared by anarchists, socialists and communists.

It is difficult to imagine different political groupings coming together to share a space and discuss fraternally without also vying for political and ideological hegemony or to win over workers to their own strategies.

But leaving this aside for the moment, one may still make the admission that the situation of the U.S. left is quite bleak. In the last few decades, when implantation in the working class seemed impossible, the far left has only managed to build in small numbers, mostly on college campuses. Many point out the breach between the revolutionary left and the working class.

A tactic that gets at this problem effectively is paramount. But how can this be achieved? How can we build a revolutionary organization within the ranks of the working class? Not through pure intellectual work, that’s for sure. What about encouraging young socialists and members of revolutionary parties to seek strategic positions as workers instead of pursuing careers as academics, “freelancers”, or isolated contractors?

The “industrialization” or “proletarianization” of left militants has been repeatedly dismissed as a failing tactic to coalesce with the organized working class and inject it with revolutionary ideas. It was a common practice among American left parties in the 60s and 70s, but the majority of activists who entered the mining, auto, steel, and garment industries with the aim of recruiting ended up isolated, with little progress to speak of for their efforts.

However, those who completely rule out this tactic should take into account that this happened during a major shift in the relation of forces between labor and capital, with the simultaneous rise of the neoliberal era and blows to the labor movement. Even if we can’t put all the blame on these “external” factors, they played a major role in the ebb of working-class militancy.

A new TUEL is an appealing idea. Under this schema, a concentration of left militants operating within certain workplaces — deemed as strategic priorities — can begin to build “bastions” of rank-and-file militancy. The piece that is missing here is the role of the revolutionary party. Who else would provide these spaces, pin down workers to come to meetings, encourage and facilitate political and theoretical discussion?

A Gradual Transition to Socialism?

Aronowitz’s enthusiasm for factory occupations and workers’ co-ops is accompanied by a balanced description of its limitations as productive units within a capitalist system. Especially refreshing is his call to “socialize banks, large-scale industry, health and education institutions.” This can only mean the socialization of the means of production under worker control.

For the working class to achieve this goal, he proposes a progressive appropriation of industries in the form of cooperatives. Adding businesses and shops one by one to a network of cooperatives, the “cooperative commonwealth” (a term he borrows from the 19th century socialists and anarchists) would at some point replace the capitalist system of production and distribution: “Workers’ and consumers’ cooperatives producing goods and services would initially compete with supermarket chains and other private enterprises and eventually replace them.”

This gradual conquest of trenches within the capitalist society takes the fight for socialism to the arena of market competition between co-ops and big capital. To be honest, it is difficult to imagine co-ops winning these battles across the board. How can a small-sized coop paying living wages to their workers/associates beat a retail mogul such as Walmart, who relies on poverty wages for its employees and large-scale economy? The role of the state in securing private profits and maintaining a sophisticated fabric of laws and rules that perpetuate individual wealth and capitalist exploitation should not be overlooked or avoided, but instead must be confronted. No socialism will ever be achieved unless the capitalist state is confronted full-on, battled, and defeated.

How to Resuscitate Labor

Towards the end of the book, Aronowitz lays out a set of proposals to build a “new labor movement.” His “ten-point manifesto” includes the elimination of no-strike provisions in bargaining agreements, a national campaign for universal income, single-payer healthcare, the fight against gender, race and ethnic discrimination at the workplace, credit unions for co-ops, and building an international labor movement able to wage war against multinationals in different countries, rather than compete with workers overseas.

He also proposes a two-fold fight for a shorter work day: pushing for legislation that mandates a reduced workday, while at the same time engaging in direct action such as marches, demonstrations and strikes. This is a very important point, and even when the author does not make the link explicit, it is closely related to the fight for the share of the profits brought in by technological improvements and the rise in productivity.

Another point stressed in the ten-point manifesto and developed in the book is the need for the rank-and-file to demand the right to create minority unions. In this type of representation arrangements, the union does not seek the right to represent the whole shop, but instead leaves open the chance for another union to represent a portion of the staff (characteristic of representative arrangements is shared by countries such as France, Spain, and Argentina). In theory, the heightened “competition” between unions compel them to be more democratic and combative. Critics have argued that in the U.S. context, where nationwide bargaining by trade is not in place, these arrangements could weaken workers’ power.

Despite criticism from some scholars and labor activists, The Death and Life of American Labor by Stanley Aronowitz offers a sharp assessment of the labor movement and a suggestive –though controversial– strategy to revive it. It should be widely read and debated among the left.